Entrepreneurship Past 50: Envisioning a Better Future

"For adults 50-plus, entrepreneurship can be an important source of income, serving as one’s main job, a side hustle, or a bridge to retirement."

Cal J. Halvorsen, PhD, MSW

Assistant Professor, Boston College School of Social Work

Project Lead and Investigator, Harvard Center for Work, Health, & Well-being

Faculty Affiliate, Center on Aging & Work at Boston College

Download PDF

Entrepreneurship—often used interchangeably with self-employment—is a major form of work among adults over age 50. In fact, 10 percent of all adults 50 and older, including those working and not, report being self-employed.1 Although working for oneself has received increased attention in the past several years, especially due to the rise in gig work, the self-employment rate among the older adult population has remained consistent over time.

For adults 50-plus, entrepreneurship can be an important source of income, serving as one’s main job, a side hustle, or a bridge to retirement. Many older adults feel pulled into entrepreneurship, seeking potential business opportunities or pursuing lifelong passions, although many are also pushed into it due to unemployment, underemployment, or age discrimination in the workplace.2–5

Yet entrepreneurship is not simply one type of work. There are many different forms of it, including gig work, independent contracting, consulting, and small business ownership.6 However, researchers who study entrepreneurship in later life, including myself, frequently group all of these forms together,7–9 often due to limitations within existing datasets and fuzzy definitions of these categories. This makes it difficult to identify differences in motivations, experiences, and outcomes between various forms of self-employment among an increasingly diverse older adult population.

50-Plus Entrepreneurship Over Time

In response, Bruna Lopez—a doctoral student at the Boston College School of Social Work—and I sought to better understand the self-employment landscape within the plus-50 population in new research supported by AARP Thought Leadership.10 Analyzing more than 1.25 million observations of respondents age 50 and older living in the United States between 2000 and 2022 with data from the IPUMS Current Population Survey (CPS),11 we were able to reveal nationally representative trends in the share of the population that engaged in entrepreneurship over time. We then looked at how this differed by age group, gender, race, ethnicity, education, income, marital status, and citizenship status, as well as health insurance coverage and access to retirement savings plans at work.

We divided our analysis between those in incorporated and unincorporated self-employment, an important distinction for 50-plus workers. Incorporated businesses are legal entities that exist independently of their owners, unlike unincorporated businesses. While incorporated businesses have some disadvantages, including the cost of setting them up, state filings, and annual fees, they also have several advantages, including personal liability protections, certain tax benefits, and a potentially unlimited life.12 For older workers, incorporating their businesses could help to protect their nest eggs if those businesses are sued or in debt, and selling their businesses could be a source of retirement income. Yet for many plus-50 entrepreneurs, unincorporated self-employment may make more sense if the goal is not to create a business that outlasts them, but to earn some extra income in a flexible way. Others may simply not know the benefits of incorporation.

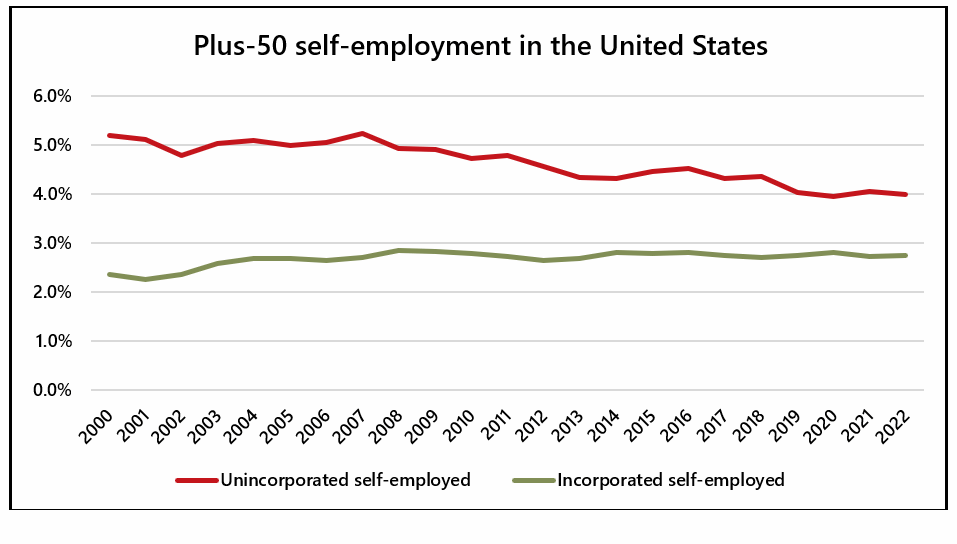

Overall, we found that unincorporated self-employment was more common than incorporated self-employment among plus-50 Americans, but that this difference has declined over time.

Source: Halvorsen & Lopez (2023), using data from the IPUMS Current Population Survey.11

Among Americans aged 50 and older, we also found that that those younger than 64 were more likely to be in either type of self-employment than those 65 and older, as were men, college degree holders, those with higher incomes, and married individuals. We found notable differences by race, Hispanic ethnicity, and citizenship status as well.

Lack of Workplace-provided Benefits

We also looked at rates of health insurance coverage and access to retirement savings programs among self-employed older Americans, as these are two important benefits that are often tied to the workplace. We found that individuals 50-plus in unincorporated self-employment made up a much greater share of the uninsured older population (about 10 percent) than the insured older population (about 4 percent). We found an even greater gap in access to workplace retirement savings programs, which are often tax-advantaged with employer matches: Among workers aged 50 and up, individuals in unincorporated and incorporated self-employment made up much greater shares of those with no access to these plans from their workplaces (about 12 percent and 8 percent, respectively) than those who were included in these plans at work (about 2 percent and 3 percent, respectively).

Separate research shows notable racial and ethnic disparities in accessing these benefits.9 Among Americans aged 50 to 64—those not yet eligible for Medicare—75 percent of White individuals in unincorporated self-employment had health insurance, compared to only 44 percent of American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) and 60 percent of Hispanic older adults in the same age group. And while 9 percent of unincorporated White individuals aged 50 to 64 were in a workplace retirement savings plan—an already low number—even fewer AIAN (1 percent) and Hispanic (3 percent) individuals in unincorporated self-employment were in these plans.

These disparities by race and ethnicity echo disparities between people in self-employment and those working in wage-and-salary work. For example, while 84 percent of wage-and-salary workers and 82 percent of incorporated self-employed Americans ages 50 to 64 have health insurance, only 72 percent of those in unincorporated self-employment do. Further, while 48 percent of wage-and-salary workers are covered in workplace-provided retirement saving programs—a rate already too low—only 22 percent of incorporated and 8 percent of unincorporated self-employed individuals are covered.9

Envisioning a Better Future for Entrepreneurs 50-plus

To promote improved health and financial well-being among older entrepreneurs, we need to expand access to health insurance and retirement savings programs, regardless of one’s place of work. Of course, some form of a universal health insurance program would do the trick, but so might state programs aimed at increasing health insurance coverage among the self-employed or forms of collective bargaining for self-employed people to obtain better rates. Creating more incentives for saving for retirement among plus-50 entrepreneurs is imperative, too, given that entrepreneurs earn less, on average, than those in wage-and-salary work7 and may therefore be more focused on immediate financial needs rather than longer-term issues of retirement financing.

Reducing these gaps is not simply a nice thing to do—there may be real economic consequences. Expanding non-employer-based health insurance access, for example, is linked to higher rates of entrepreneurship.13–15 This could be good for our entire economy.

Our findings also highlight how self-employment can be seen both as an opportunity and a constrained choice among plus-50 adults when few other opportunities exist.3,5 Groups with higher rates of incorporated self-employment, including citizens, higher-income individuals, and those with college degrees, are also more likely to have employees,16 indicating growing businesses. Conversely, many people may pursue unincorporated self-employment for lack of other employment opportunities, including due to discrimination or bias against one’s age, abilities, or immigration status, among other factors,2,17,18 or as a bridge to retirement.19 More education to understand the differences between incorporated and unincorporated self-employment and assistance in helping entrepreneurs 50-plus to incorporate their businesses may lead to improved personal and business outcomes.

A better future for entrepreneurs over age 50 is a better future for all Americans. A system in which they can easily and affordably access health insurance and retirement savings programs will not only reduce benefits disparities between incorporated and unincorporated entrepreneurs who are 50-plus, but may make entrepreneurship a more enticing option for all older Americans while offering economic benefits to society overall.

References

1. Halvorsen, C. J., & James, J. B. (2020). Self-employment trends among older Americans. Center on Aging & Work at Boston College. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4404984

2. Halvorsen, C. J., & Morrow-Howell, N. (2017). A conceptual framework on self-employment in later life: Toward a research agenda. Work, Aging and Retirement, 3(4), 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waw031

3. Kautonen, T. (2008). Understanding the older entrepreneur: Comparing third age and prime age entrepreneurs in Finland. International Journal of Business Science and Applied Management, 3(3), 3–13.

4. Singh, G., & DeNoble, A. (2003). Early retirees as the next generation of entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(3), 207–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-8520.t01-1-00001

5. Weller, C. E., Wenger, J. B., Lichtenstein, B., & Arcand, C. (2018). Push or pull: Changes in the relative risk and growth of entrepreneurship among older households. The Gerontologist, 58(2), 308–319. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw145

6. Pitt-Catsouphes, M., McNamara, T., James, J., & Halvorsen, C. (2017). Innovative pathways to meaningful work: Older adults as volunteers and self-employed entrepreneurs. In E. Parry & J. McCarthy (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Age Diversity and Work (pp. 195–224). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-46781-2_9

7. Halvorsen, C. J. (2021). How self-employed older adults differ by age: Evidence and implications from the Health and Retirement Study. The Gerontologist, 61(5), 763–774. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa132

8. Kautonen, T., Halvorsen, C., Minniti, M., & Kibler, E. (2023). Transitions to entrepreneurship, self-realization, and prolonged working careers: Insights from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 19, e00373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2023.e00373

9. Halvorsen, C. (2023). Unsupported economic heroes: Illustrating disparities in health insurance and retirement plan coverage among American entrepreneurs ages 50 to 64. SSRN. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4489387

10. Halvorsen, C., & Lopez, B. (2023). Entrepreneurship Past 50: Self-Employment Trends — 2000 to 2022 (SSRN Scholarly Paper 4651610). https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4651610

11. Flood, S., King, M., Rodgers, R., Ruggles, S., Warren, J. R., Backman, D., Chen, A., Cooper, G., Richards, S., Schouweiler, M., & Westberry, M. (2023). IPUMS CPS: Version 11.0 (11.0) [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS. https://doi.org/10.18128/D030.V10.0

12. How—And why—To incorporate your business. (n.d.). Entrepreneur. Retrieved January 9, 2024, from https://www.entrepreneur.com/starting-a-business/how-and-why-to-incorporate-your-business/77730

13. Liu, L., & Zhang, Y. (2018). Does non-employment based health insurance promote entrepreneurship? Evidence from a policy experiment in China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 46(1), 270–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2017.04.003

14. Fairlie, R. W., Kapur, K., & Gates, S. (2011). Is employer-based health insurance a barrier to entrepreneurship? Journal of Health Economics, 30(1), 146–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.09.003

15. Bailey, J., & Dave, D. (2018). The effect of the Affordable Care Act on entrepreneurship among older adults. Eastern Economic Journal. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41302-018-0116-7

16. Hipple, S. F., & Hammond, L. A. (2016). Self-Employment In The United States. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.bls.gov/spotlight/2016/self-employment-in-the-united-states/pdf/self-employment-in-the-united-states.pdf

17. Williamson, M. W. (2023). Understanding the Self-Employed in the United States. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/understanding-the-self-employed-in-the-united-states/

18. Fisher, M., & Lewin, P. A. (2018). Push and pull factors and Hispanic self-employment in the USA. Small Business Economics, 51(4), 1055–1070. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-9987-6

19. von Bonsdorff, M. E., Zhan, Y., Song, Y., & Wang, M. (2017). Examining bridge employment from a self-employment perspective—Evidence from the Health and Retirement Study. Work, Aging and Retirement, 3(3), 298–312. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/wax012